Cinematic Switzerland. Lausanne between green, blue and a mind movie

Ileana Ramirez

I would like to go on a big trip [...]. I would like to film everything. Everything that moves me. Faces, roads, passing cars and buses, train stations and airplanes, rivers and oceans, streams and streams, trees and forests. Fields and farms and even more faces. Food, interior, doors, windows, meals being prepared. Chantal Akerman[1]

That Saturday night of my first weekend in Switzerland, to be more specific, in Dreispitz where my studio was located and where I lived for almost half of 2023, after a long walk along the Rhine river in the middle of a summer day, I dedicated myself to unsuccessful searches on the internet. The first thing I typed on the keyboard of my computer was "movies filmed in Switzerland." The answers that popped up back on the screen of my laptop were very random: action movies, some more romantic ones. It seems that mountains and lakes arouse a fascination between heartbreak and suspense. I was not sure whether the idea of understanding a country through a filmography was the most appropriate thing, but I embarked on the Google search adventure that led me to a film that determined my next days and weekends in a very small country whose great and sacred mountains hide the most fascinating mysteries. Maybe I should clarify that I arrived in Basel in July 2023 thanks to a curatorial residency that I was able to do with the support of Pro-helvetia, Atelier Mondial and Ausstellungsraum Klingental. They were a very intense, dynamic, and unforgettable five months. I arrived in Basel in July, it was summer when many people were on vacation, and art activities had a slight pause that allowed me to get closer to the cities, observing their architecture, the movement of their inhabitants, and understanding that in a short time I would also make it mine.

After watching the short film that Jean-Luc Godard dedicates to his friend, the Swiss film critic Freddy Buache, (Lettre à Freddy Buache, 1982), I quickly decided, with an urgency (maybe similar to the one Godard depicts in the film when he describes the emergency of the cinema and its agonizing status), to head off to the SBB railway station

and take the train to travel around Switzerland. My destination was Lausanne, a city that Godard depicts as having a vertical topography from the top of its mountains to the bottom of Lake Léman or Lake Geneva, situated across the French Alps. Going to Lausanne meant to recreate the shots and scenes of some of Godard's films: street scenes

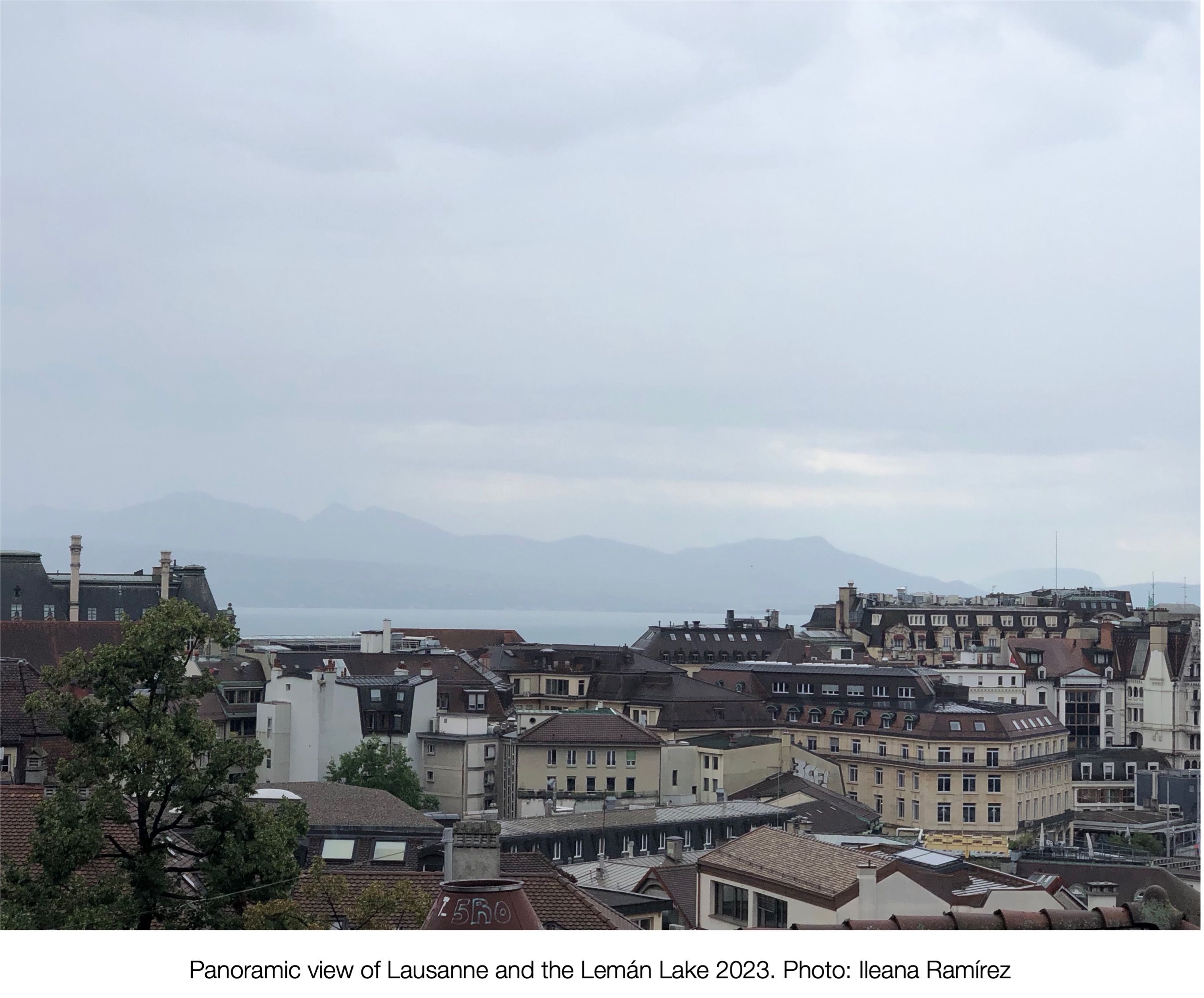

where passersby are portrayed moving between bridges, and even public elevators that try to compensate for the particular topography of this city. That day was not the most summerlike of all; a downpour of rain was falling, and I was not at all prepared, so I had to improvise to find a place to shelter among the slopes of the streets of a very Still shortfilm Jean-Luc Godard, A Letter to Freddy Buache (1982) vibrant and quite dissimilar city with medieval architecture, but with an imprint of industrial and modern development, with art deco buildings and a sixties style that reminded me of some areas of the city of Caracas. The first thing I did when I arrived in the city was to climb up the stairs of the Scalier du Marché to the hill, but before I did, I passed by the Palais de Rumine, a 19th-century building Florentine Renaissance style designed for the use of the public as the library of the University of Lausanne, among other facilities. After a long and tiring walk, I reached the top, where the Lausanne Cathedral is located. The intimidating and beautiful medieval architecture was flooded with tourists who were doing the same thing as me. Outside, there was a viewpoint where I wanted to see the beauty

of Lake Geneva and the Evian Mountains, but I had to accept the fact that this was not the best day for landscape appreciation since the bad weather overshadowed the summery experience.

My improvised trip was transformed into a journey of new images, so transitory and fleeting, ready to be forgotten. However, I kept fresh the memory of the film that Godard dedicated to his friend, although it was initially commissioned by the city of Lausanne to create a film commemorating the city’s 500th anniversary. The filmmaker had refused to meet the conventional demands of the genre of expository documentary, and his film was rejected, so I wanted to rediscover it, as if some of the anonymous faces in the scenes were familiar to me. Walking between steep slopes, I found some closed movie theaters. I had read that Lausanne has the largest number of cinematheques in Switzerland and is famous for its large number and variety of film festivals. Even Godard had made a film for TV Télévision Suisse Romande (TSR) called Sauve qui peut (la vie), made for Swiss television under the title Voyage à travers un film.

I'd go up, then come down again, because it is a city that rises and falls.

In this city, I thought there was something between the sky and the water

While shooting I saw something between green and blue

Do you remember when Wittgenstein said We'd made a mistake and called bluegreen

That’s perfect for Lausanne changing names[2]

In my own movement throughout the city, a somewhat erratic and open displacement was already defining some elements as layers and levels with a spatial variety that could paradoxically play with the names of the shots in a film shoot. It is definitely a modern city, with trains, subways and a land and water transport network waiting at its ends. From my arrival by train, then a few kilometers downhill on foot from the Lausanne cathedral, crossing Les Escaliers du Marché among very touristy shops, it is known that anyone who is new to Lausanne takes the bait of these architectural curiosities the Léman Lake was still very far away. After walking restlessly, I was back again at the main train station, but I continued my wandering walk, and among lonely streets, some residential, I began to discover that the urban blends in with an area of sophisticated and elegant hotels until I stumbled upon the Château d’Ouchy a majestic edification in the small district of Ouchy from medieval times with lush gardens that carefully do not overflow the promenade along the Léman.

It was already after 5:30 p.m., and my friends had recommended that I return to Basel by taking the Golden Pass railway through the mountains of the Alps. On the other hand, I was already by the piers and in my stubborn curiosity, I boarded the small boat named Rhone with a tide of people, families, and children. I was alone, as I was on practically all my trips. The journey from the port of Lausanne had the first stop in Vevey and then in Montreaux. At that time, the rain had stopped, and the long-awaited summer sun began to rise up, appearing barely just as a sunset.

Sailing is also a cinematic experience, especially when in the moving image, the frame is the train that moves almost as fast as the ferry and goes to the edge of the coast of the medieval cities, but the locomotive wins and moves on. This scenery reminds me of what Roland Barthes writes in the letter he dedicates to the director Antonioni: "The artist never knows if what he wants to say is a true testimony about the world as it has changed or the simple egotistic reflection of his nostalgia, or his desire: an Einsteinian traveler, he never knows if what moves is the train or spacetime, if he is a witness or a man of desire.”[3]

Upon arriving in Montreux I disembark from the small boat and take a brief walk along the boulevard, which is crowded with people, tourists, and vendors. A little further on, there is a group of semi-modern buildings, there are many hotels; and I find out that Freddy Mercury lived in one of the hotels near the promenade, where he would also record up to six albums. Gone was the adventure of the day in Lausanne, the movie theaters and surely the places that Godard visited, such as the Swiss Cinematheque, the Capitoline Cinema, the Modern Cinema, or searching among people to identify the anonymous faces waling down the streets of this busy city. Finally, I found the way back home.

In three more hours, I was back at the long-awaited SBB CFF railway station in Basel, where I could always contemplate some immense canvases that portray the lakes of the three cantons. When I arrived at my studio and thought about my entire journey, I couldn't believe how much my body allowed me to travel an immeasurable panorama of images that allowed me to assimilate despite the rain and the failed searches for the lonely trains.

Lausanne was already a city that is built on architectural panoramas of dense urban developments, and my experience while touring it, although

this time in a clumsy and haphazard way, would awaken in me the next image and montage stories for my days to cinematic language, "transporting" the viewer through space and creating a multiform travel effect. The fascination involved the same means: it produced a visual space in motion. These "moving panoramas" were decisive in developing the fiction film. The language of cinema was not born from static theatrical visions but from urban movements.

Although I did not shoot a film, the experience of cinema from its places of archives, projection and production influenced my approaches to the different manifestations of art that I was able to appreciate during my curatorial residency. I was motivated to create stories and leave them in my memory, my personal archive of consciousness, by recording video footage. Narratives may depend on our own spatial and optical movement with our limitations because the subjective gaze is the most honest, and that gives meaning to a key in the way I approach the challenging nature of the images; they appear when I appear, as to say that I am physically present, collecting visual memories and building up future stories to be told and lived through.

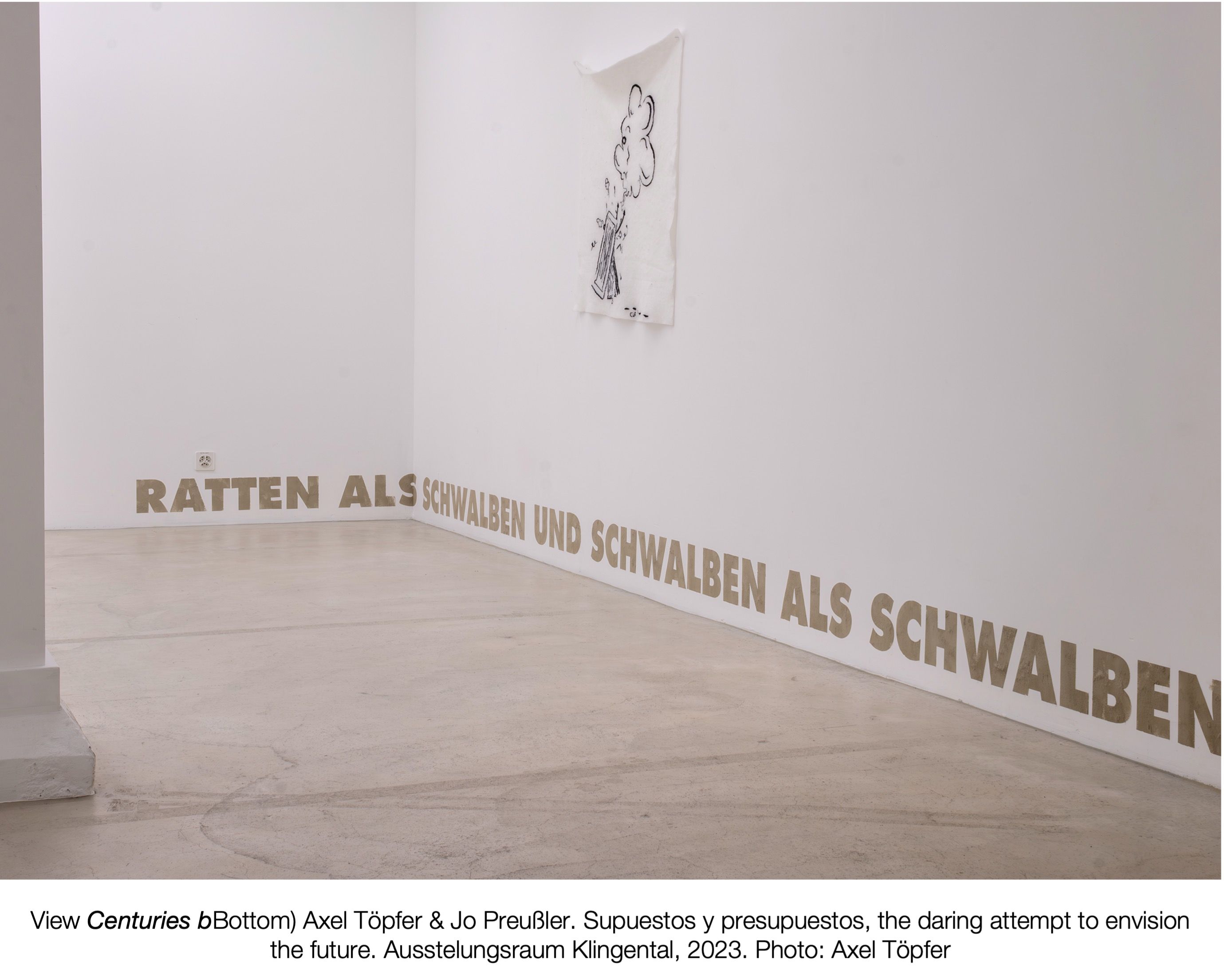

In the context of Supuestos y presupuestos, the daring attempt to envision the future[4], an exhibition I curated at Klingental as part of my curatorial residency, a diverse range of concepts regarding the city were fundamental to the core statement for the art show. Especially important was the representation of the moving image within the boundaries of a city for the migrants, the displaced, and the individuals who are forced to be nomads within the notion of a city in diverse circumstances. The intricate interplay between literature, history, and fictional elements that surround a vanished city is what artists Axel Töpfer (GDR, 1977) & Jo Preußler (GDR, 1977) proposed with their mind movie, Centuries, a series of brief narratives displayed throughout the room gallery, that requires the viewer to move around to see them and read them in order to perform the cinematic experience. The site-specific consists of a group of sentences taken from The Invisible Cities (1972) novel by Italo Calvino, unfolding an odyssey through these imaginary cities for and with the author for his 100th birthday . Each one of the letters

[5] of the sentences were composed by water and sediment from the Rhine, which were displayed along the entire length of the Klingental gallery room. The mind movie in this case, is structured so that the viewer performs the movement to assemble each story out of its parts. In that sense, it makes me think about city panoramas like a specific time frame but at the same time as a big full story like the places I visited in this country, where the practice of cinema accompanies an expanded time in a transit space of urban and mountainous layers.

In another installment, there will be time to narrate the days in Locarno and its film festival in a town full of extravagant villas located on the hills of the green mountains that remind me of some neighborhoods in Caracas. Cinema always finds the city and the city always establishes a dialogue with which to explore it, with its passers-by, with its observers, with those who are new and barely discover it, whether Caracas, Basel, Lausanne, Locarno, Zurich, Bern, Zurich, Lucerne and all those on the old train route map hanging on the wall of my studio that I used to

mark when returning home.

Ileana Ramírez Romero

Dec, 2023

[1] Atlante delle emozioni. In viaggio tra aere, architettura e cinema (2019)Bruno, Giuliana. Pag. 3.

[2]Lettre à Freddy Buache [A Letter to Freddy Buache] (1982) shortfall by Jean-Luc Godard.

[3] Querido Antonioni… (by Roland Barthes) https://www.edder.org/?p=1416. Roland Barthes,

[5] https://backend.ausstellungsraum.ch/site/assets/files/2307/ausstellungsraum-klingental-supuestos-y-presupuestos-0p3t.pdf