Verantwortung

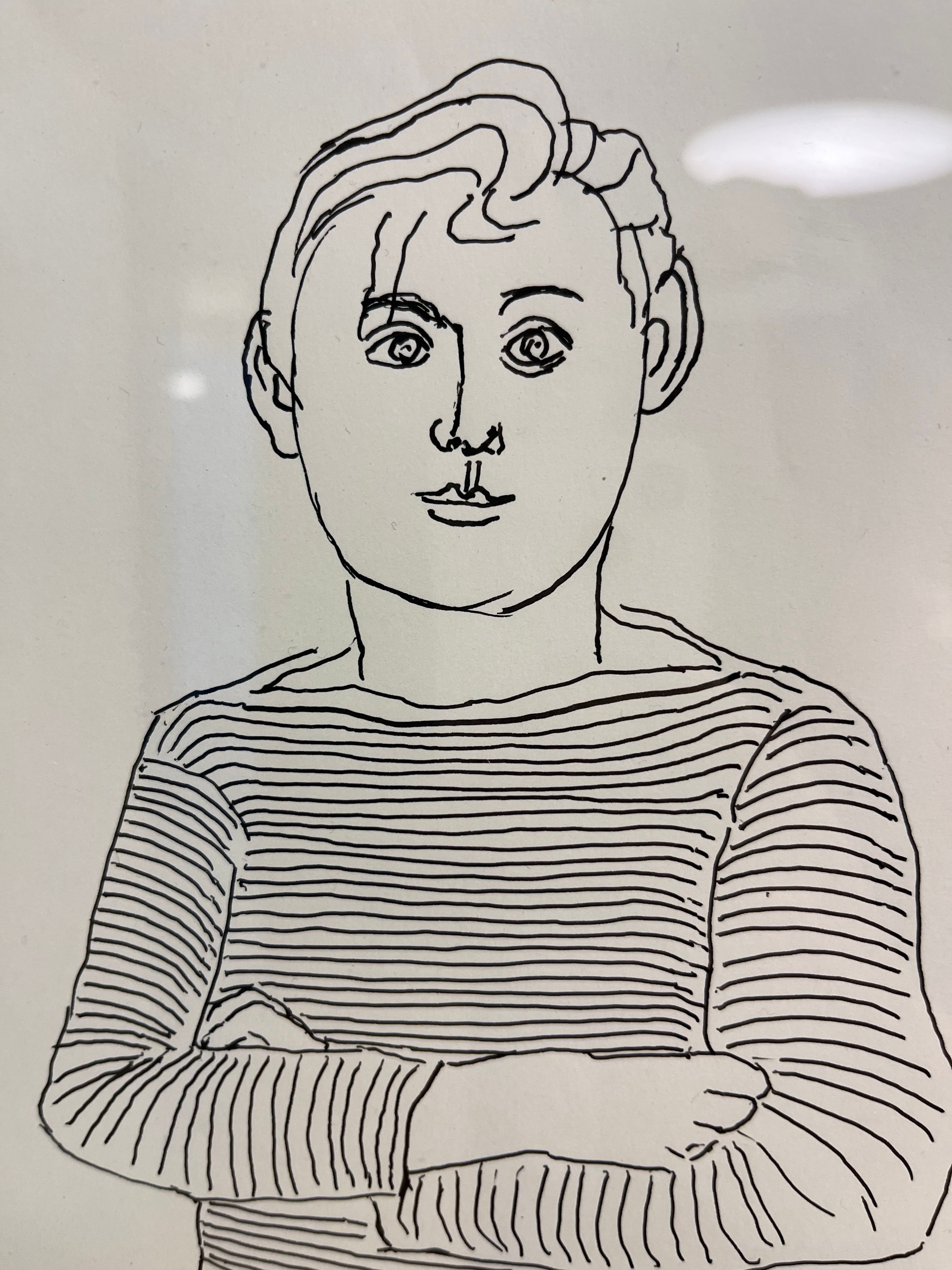

Juan Zen

About fifteen years ago, when I travelled to Bangkok, I had the feeling that the Chao Phraya River was in flood. From my hotel room at the Royal Orchid Sheraton, which had been paid for by my parents-in-law, it certainly looked that way. The water was brown, and all kinds of debris drifted along its surface. Had it been the Rhine in Basel — the river I know best — it would definitely have counted as high water.

Just a few hours earlier I had still been sitting in the plane in Zurich, on an Edelweiss flight that could not take off because the pilot had discovered damage to the turbine. Around me were two hundred people who were looking forward to their holidays in Thailand and who, during the extended waiting time on the runway, voiced their anticipation, thoughts and backgrounds more or less loudly — like a many-voiced canon floating through the cabin.

After we were asked to leave the aircraft and spend the night in the airport hotel in Kloten — giving the Edelweiss mechanics time to fix the turbine — the journey that followed was fantastic.

What has stayed with me, although I tend to forget almost everything very quickly, was a prawn dish I still think of whenever I go to a Thai restaurant. A white sweet-and-sour soup with pink prawns, served with rice on a terrace that stretched out over the turquoise sea.

I thought of this dish on a late Sunday evening when I decided to go to a Thai restaurant to pick up something to eat at home on my sofa. The restaurant had a similar dish on the menu, but I didn’t want to ruin the memory with a mediocre Basel version, so I chose Bai Kapao with chicken instead.

While I waited, I noticed the many Uber Eats and JustEat couriers who were picking up orders for those who had remained on their sofas that Sunday evening. The restaurant has fifty seats, all of them empty except for one. Instead, a queue formed — people in worn Decathlon rain jackets, with crookedly fastened motorbike or bicycle helmets, collecting the paper bags in which the cooked meals left the restaurant.

My thoughts went back to the afternoon and to Melissa, who had told me at her exhibition “Verantwortung” that she works for JustEat to earn the money she needs to live and to make her art. During our conversation she showed me an article she had written for a trade-union magazine, which lay on a table in the exhibition space. I leafed through it and read that she earned 22 francs an hour delivering meals from the city’s restaurants to its households.

The exhibition was organised by the project space Die Treppe – Bildungszentrum and took place in the Iselin neighbourhood centre, in the middle hall of the Westfeld complex. Opening hours were Saturday and Sunday from 1–7 p.m., and on Sunday from 1–5 p.m. On the table where I was reading Melissa’s text lay other books as well, many devoted to Gruppe 33, an anti-fascist artists’ group founded in 1933 in Basel in opposition to the conservative tendencies among Swiss painters, sculptors and architects.

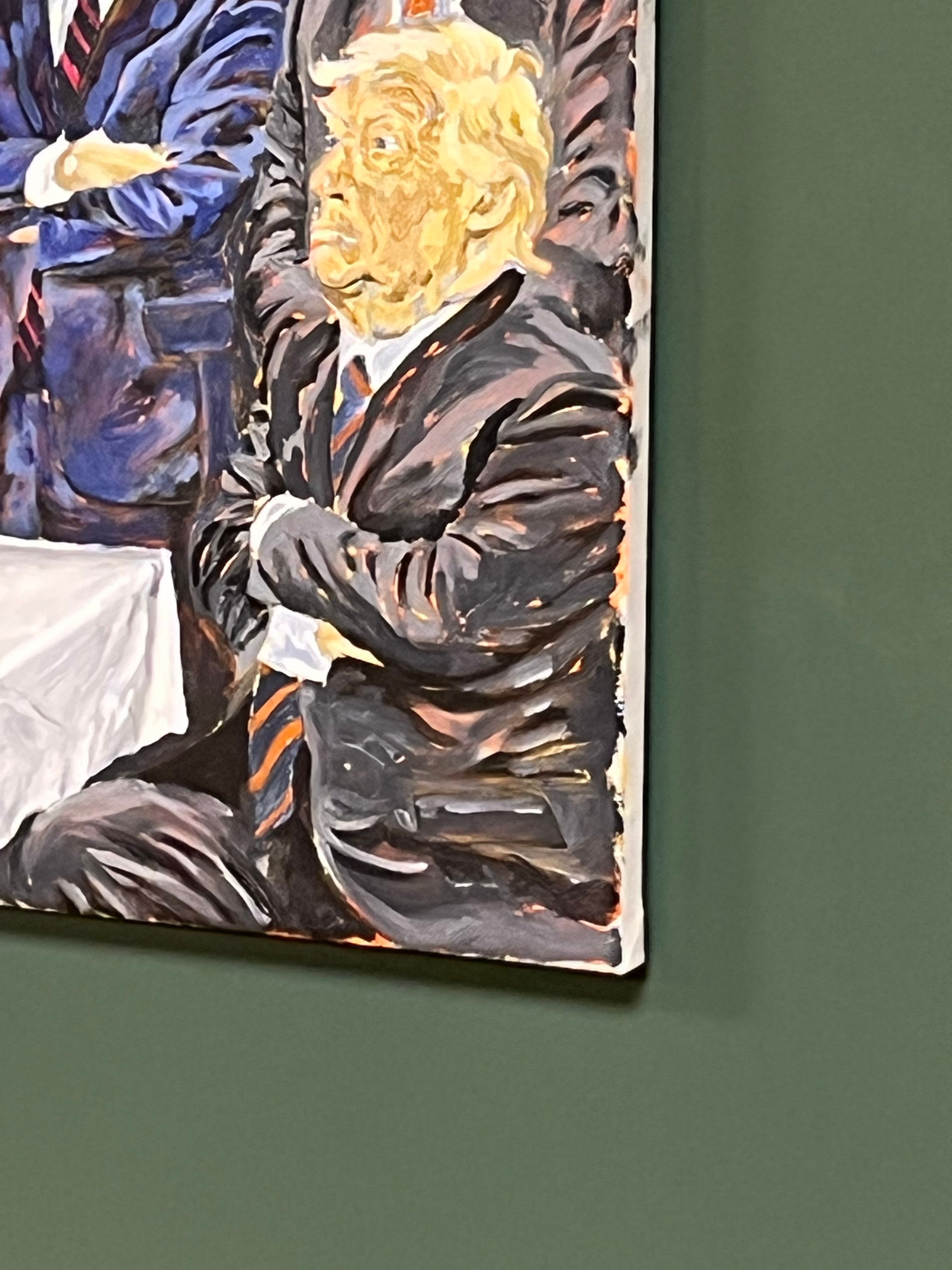

One member of this group was Rudolf Maeglin(1892 - 1972). He came from an upper-class background: his father a wine merchant, his mother from a family of Basel silk manufacturers. Although he studied medicine and passed his state exam at 27, he decided soon afterwards to become an artist. He built himself a studio house in the Basel neighbourhood of Kleinhüningen and began painting portraits of his neighbours, who were mostly chemical-plant and harbour workers. Alongside these portraits, he also documented the city’s advancing industrialisation, painting construction sites such as the Mustermesse as well as the building of the Dreirosen Bridge, which connects Kleinbasel to Grossbasel and at that time linked the working-class districts of Kleinhüningen and St. Johann.

One painting in particular stayed with me during my visit to the exhibition “Verantwortung”: the one reproduced in the Mäeglin catalogue next to the trade-union magazine containing Melissa’s text. It shows people spending their free time along the Wiese — a river that flows into the Rhine in that neighbourhood — relaxing after work, playing, kissing, and bathing in water that Mäeglin did not paint blue but oily brown. A brown like the one I had seen fifteen years earlier, looking down from the fifteenth floor of that hotel on the Chao Phraya.

translated with chatgpt - so not very accurate