Of Curatorial Contexts, Christ and clever Ingenious Women

Q.U.I.C.H.E.

In the 21st century, the curatorial practice of European museums is very often and rightly concerned with correcting past mistakes and with successively overcoming horrific mechanisms of exclusion, suppression and erasure from public perception. As an opposing phenomenon, the writer of this text who is merely an amateur in museology and theory of aesthetic perception repeatedly makes the astonishing observation that most exhibition visitors who have not undergone a "déformation professionelle" prefer to look at artworks in a work-immanent rather than contextual manner. The discussions at the phenomenal Jeff Wall exhibition at the Fondation Beyeler, both secretely overheard and conducted by the author himself, mostly revolved around pictorial motifs on the representational level, visual impressions, composition, facial expressions, colours and brightness, rather than colonial criticism, media-theoretical backgrounds or cultural-historical references.

It is therefore unfortunate when the marketing, communication and exhibition texts of exciting exhibitions de facto refuse to deal with specific works themselves and focus almost exclusively on the historical or conceptual context. Marketing departments understandably have no understanding of art; they would probably fulfil their tasks worse if they had to deal with actual intellectual content. For curators of state museums in particular, the balancing act is more challenging: what do I want to convey to the public, what do I HAVE to convey to them because of my mission and my public funding? How do I manage to ensure that the urgent themes behind the works receive enough attention without the exhibits becoming arbitrary and interchangeable?

These thoughts all came to mind when I saw part of the "Ingenious Women" exhibition. In the sombre and mostly ignored “Grafikkabinette” on the first floor of the main building, several works on paper by female artists from the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries are on display. These include Christ and the Adulteress, a 1575 engraving by Diana Scultori, called Mantovana. The carefully researched work text on the adjacent panels displays the artist's biography in a nutshell and mentions the two inscriptions on the sheet. One is the dedication to Eleonora of Austria, Duchess of Mantua, and the other is the papal printing privilege, which must have been extraordinary for a woman of that time.

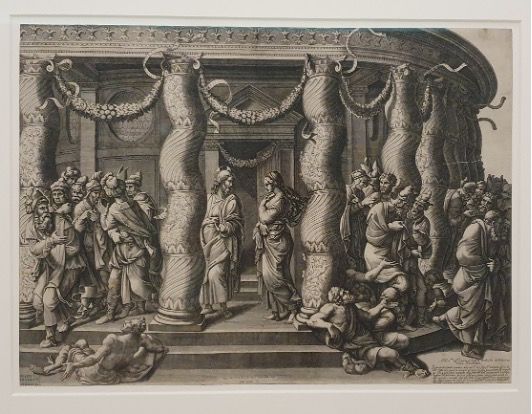

But what can actually be seen in the engraving? The composition, which was probably originally designed by the architect and painter Giulio Romano (14499 to 1546), shows Christ and the young woman in the peristyle of a sacred central building. Its winding columns perhaps mark it as the Temple of Solomon, indirectly alluding to Christ's wise justice. Numerous men, some hurrying away, others looking back in annoyance, flank the two main figures in front of the central portal of the temple. Their deliberately strange clothing conveys them as antagonists, in casu they are the Pharisees. Like many of Giulio Romano's works, the overall design of the engraving is reminiscent of works by his teacher Raphael. The patron saint of harmonious composition and his workshop had designed tapestries for the Sistine Chapel 50 years before Diana Mantovana's engraving. The scene of the Healing of the Lame takes place right in the centre of very similar columns: Giulio Romano and later Diana Mantovana obviously reused the motif for Christ and the Adulteress. Nevertheless, this sheet is characterised by its very own, completely convincing balance. The figures at the centre of the action are enchanting: the wise, forgiving, not moralistically overzealous Jesus is indeed something of an ideal image of a human, and not only because of his posture and perfect aesthetic harmony. His morals set him apart from his self-described followers today, who do not hesitate for a moment to cast the first stone at alleged sinners! Be it abortion bans, headscarf obligations or the bombing of children's hospitals: Jesus as the compositional highlight of the left half of the picture, the culmination both of the pictorial human pyramid and the proverbial human love, he would probably be horrified!

The absolute eye-catcher of the work is, of course, the lady at the top of the stairs, the entry to the right-hand half of the painting. The same height as Christ (!!!!), she lowers her gaze in a grateful gesture of humility without appearing submissive, helpless or undignified. The folds of her antique-style dress are splendid examples of Aby Warburg's "Bewegtes Beiwerk" - the braided hair would perhaps only have been more beautifully done by Leonardo or later by Élisabeth Vigée-Le Brun. Her body nestles perfectly against the elegant columns - she herself becomes the ennobling decoration of Solomon's temple, so to speak. The Lady isn’t a tramp - she’s a Goddess.

Of course, none of this fits on a small wall panel - but it helps us to better understand why this work in particular is in no way inferior to the "Ingenious Women" exhibition on the ground floor.

(HE)